The More We Get Together

Walk into a high-performing school and chances are you will find a group of teachers working and learning together. They might be planning future lessons, problem-solving, analyzing data, discussing strategies, or reflecting on their teaching. If the collaboration centers around teacher and student learning, it will likely lead to increased student achievement (Hord & Sommers, in press; Hargreaves & Fink, 2006; DuFour & DuFour, 2006; Lambert, 1998; Lieberman, 1996).

When teachers work together, they participate in a valuable exchange of ideas, learning new things and contributing to each other’s knowledge while improving the quality of their working relationships. Sustained collegial work leads teachers to become aware of their obligation to work together toward schoolwide problem solving and enhancement of their own teaching behaviors (Barth, 1990; DuFour & Eaker, 1998; Hord & Sommers, in press). Stigler and Hiebert (1997) state:

Despite the fact that research indicates that this collaborative, ongoing type of professional learning is more effective in promoting school improvement and increasing student achievement than the typical short-term conference or workshop (Ancess, 2000; Joyce & Showers, 2002; Neufeld & Roper, 2003; Sparks, 2002), it has been slow to take hold, especially in the low-performing schools that arguably need it most. These schools often seem stuck in the search for a quick-fix solution or one-shot workshop presented by an outside expert. While there can be a place for this type of training occasionally, it must be acknowledged that little deep learning takes place in this setting because of minimal opportunities to truly understand the purposes and implications of the concepts, to practice strategies, or to receive constructive feedback.

Teacher collaboration, on the other hand, provides a less formal and more interactive venue in which teachers can deeply discuss and question ideas and strategies at a pace that is comfortable to the group. Additionally, the ongoing nature of these groups offers teachers a chance to discuss a strategy or issue, break from the group to apply the strategy or contemplate the learning, and then bring ideas and experiences back to the group to share, analyze, and refine.

A teacher study group is a group of dedicated trusting educators…

Professional learning through teacher collaboration is often the established expectation of a school or district that recognizes the value of such cooperation. These schools or districts often operate as formal professional learning communities (PLCs) where teacher study groups are recognized as learning opportunities for teachers within the broader learning culture of the PLC. Teachers who work in schools that don’t operate as PLCs, however, sometimes organize a grassroots effort to work together out of desire or the need to reach out for assistance from others. These grassroots efforts should be commended and encouraged. While well worth the effort, collective learning can be difficult and time-consuming as team members work to schedule common planning times, plan for meetings, and maintain a regular schedule with follow-up. Leaders who recognize the efforts of teachers attempting to establish study groups and support them by providing sheltered time, space, and resources that facilitate this collaboration should be applauded as well.

Terms typically used to describe this type of collaboration include “teacher study groups,” “teacher inquiry groups,” “professional inquiry groups,” and “teacher networks.” But what exactly is a teacher study group? It might be best to begin with what a teacher study group is not. A teacher study group is not an in-service where one “expert” presents ideas or explains how to implement a strategy. A teacher study group is not a staff meeting where school or department business issues are discussed. It is not a clique where complaints about students, colleagues, policy, or administration are aired.

A teacher study group is a group of dedicated, trusting educators committed to professional growth and mutual support. It is a group that gathers, preferably voluntarily, to openly reflect on goals, instructional practice, student learning, and theory. The study group could be a fairly large group of educators that assembles to find solutions to a significant problem (low student test scores in reading or high drop-out rate, for example), or it could be a small grade-level or content-area group that gathers to discuss such topics as implementation of reading workshops or the viability of portfolio assessments. Regardless of the type or size of the study group, there are steps and details that help ensure its success.

Phases of the Study Group Process

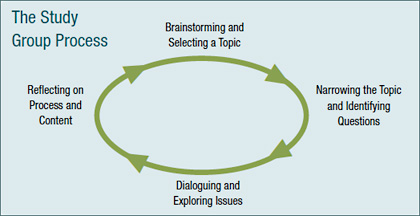

In their book Teacher Study Groups, Birchak et al. (1998) outlined four phases of the study group process that teachers progress through as they move within and among topics. The phases are

- brainstorming and selecting a topic;

- narrowing the topic and identifying questions;

- dialoguing and exploring issues; and finally,

- reflecting on process and content.

We encourage teachers as they begin to work through the four phases, to keep in mind the importance of discussing and studying research findings and considering practices that are supported by a strong research base.

Brainstorming and Selecting a Topic

The first phase involves identification of a topic. Topic ideas often emerge from an examination of concerns at the district, school, or classroom level. Perhaps newly implemented policies, school assessment information, or instructional problems are issues for the staff at the study group’s school. These are all topics that a study group could consider. Keep in mind that topics should be directly related to school goals and student achievement. Once a topic has been determined, teachers interested in that topic will commit to participate in that specific study group.

Norms and meeting logistics should be established and refined in the first few meetings. These initial meetings also offer an excellent opportunity for the group members to get to know one another and to build the foundations of an open and trusting relationship, which is critical if a meaningful dialogue is to ensue.

Narrowing the Topic, Identifying Questions

This phase of the study group process includes thinking about resources and strategies that will facilitate inquiry. It also allows group members the opportunity to focus attention on issues that are personally relevant (Birchak et al., 1998).

Dialoguing and Exploring Issues

The third phase of the process involves a series of meetings in which the issues and ideas are explored in depth. This phase is really the core of the process. The group first discusses these issues and ideas. Members often leave this meeting with an assignment—to read a chapter or journal article, practice a strategy, or gather more information or data. At the next meeting, the assignment results are shared and discussed. Group members often study research findings in this phase. Evidence-based and best practices are identified and discussed, then tried out. Sometimes group members find it helpful to receive input from outside experts or peers who are dealing with similar issues. It is important that teachers in the group feel comfortable enough to admit what they don’t know. Developing this comfort level requires spending time building and strengthening relationships among group members. The role of the facilitator in this phase is central. The facilitator is responsible for ensuring equitable participation by all members and asking reflective questions that lead to deep and meaningful conversations. The facilitator keeps the conversations moving in a direction that focuses on the identified issues. Sometimes conversations veer in an unintended direction, which is acceptable as long as the study group members agree.

Reflecting on Process and Content

The phase in which study group members reflect on the process and content of the study group is an important one. It is helpful to pause at specific increments of the phase, perhaps once a semester, in order to assess the progress of the group. Group members can discuss what has been learned and what questions still exist. The team needs to make a determination at that point about whether to continue the discussion in its current direction, adjust the topic slightly and follow that path, or end the discussion and begin the brainstorming process again to identify a different topic.

The Study Group in Action

To illustrate how a study group might work, let’s look at a group of teachers you might see at a typical elementary school.

Judy, Maria, Jerome, Dee, and Al are all second-and third-grade teachers. Through several discussions in the teachers’ lounge, the group members discover that they are all troubled by the low reading comprehension test scores of several of the students in their classrooms. Maria is taking a university course as part of her master’s program and mentions that her professor has recommended a recently published book that may offer the group some guidance. She asks the group members if they’d like to participate in a study group to discuss, learn about, and implement some of the strategies outlined in the book. All of the teachers agree. Maria, serving as the facilitator, approaches the principal about purchasing the book for each member of the group. The principal agrees, and the group schedules their first group meeting. Prior to the first meeting each group member commits to reading the first chapter, which will be the topic of discussion that day.

Study groups can become more than a way for teachers to find solutions to the educational problems they face.

At the first meeting, discussions initially center around meeting logistics (selecting a comfortable and convenient meeting place and time, arrangements for group member absences, refreshments, etc.). They then begin talking about the first chapter of the book. As the discussion progresses, the group members decide that proceeding lock-step through the book, chapter by chapter, would not meet their needs. They collectively agree to begin with the chapters that address effective questioning and inferential skills—areas they agree that their students could benefit from the most.

The group spends the next 2 months meeting on a weekly basis, covering a chapter each week. Group members participate in a deep discussion about reading comprehension theory, best practices, and specific strategies outlined in the book. They often bring in research or professional articles that support or counter the author’s opinion. In between study group meetings, group members practice reading comprehension strategies in their classrooms. They then return to the study group to discuss and compare their efforts—successes and failures—with their peers. Toward the end of the 2-month period, the group members agree to continue to regularly implement the comprehension strategies that they all agreed might be effective and to reconvene at the end of the semester to compare the reading comprehension assessment results of their students. They plan to make a decision at that time, based on the assessment results, about whether they want to continue their exploration into reading comprehension theory and instructional strategies or explore additional areas in which their instructional practices might be improved.

As with the group just described, study groups can become more than a way for teachers to find solutions to the educational problems they face. The groups can be an extremely beneficial professional development approach that impacts the classroom practice of the teachers involved and can provide a framework for collaboration that impacts the learning culture of the school as a whole. As Birchak et al. (1998) state:

A study group promotes an investigative environment that supports individually directed growth and influences the school community at large. While a study group is not the answer to every question and every problem, it does represent a movement away from divisive and isolated competitiveness, toward synergistic collaborations. It is a seed that can encourage teachers to believe in their right and their ability to ask and investigate questions, and to propose solutions. Through the study group, teachers confer upon themselves the respect often denied by bureaucratic traditions; they affirm themselves the educational experts and acknowledge their own professionalism. (p. 143)

When the staff is focused on student learning, this type of professional collaboration can have a direct and positive impact on student achievement (Bobbett et al., 2000; Levine & Lezotte, 1990; McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006; Miller, 1982). Administrators, consider establishing teacher study groups as an effective professional development approach that will impact the effectiveness of teaching and learning in your school. Teachers, consider participating in an established study group at your school. If there is no established group, start your own. You, your fellow educators, and most importantly, your students will benefit greatly.

References

- Ancess, J. (2000). The reciprocal influence of teacher learning, teaching practice, school restructuring, and student learning outcomes. Teacher College Record, 102(3), 590–619.

- Barth, R. S. (1990). Improving schools from within. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Birchak, B., Connon, C., Crawford, K. M., Kahn, L., Kaser, S., Turner, S., & Short, K. (1998). Teacher study groups. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

- Bobbett, J., Ellet, C. D., Teddlie, C., Olivier, D. F., & Rugutt, J. (2002, April). School culture and school effectiveness in demonstrably effective and ineffective schools. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Research Association, New Orleans.

- DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. Reston, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- DuFour, R., & DuFour, R. (2006–2007). The power of professional learning communities. National Forum of Educational Administration and Supervision Journal, 24(1), 2–5.

- Hord, S. M., & Sommers, W. A. (In press). Leading professional learning communities: Voices from research and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.) Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Lambert, L. (1998). Building leadership capacity in schools. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Levine, D. U., & Lezotte, L. W. (1990). Unusually effective schools: A review and analysis of research and practice. Madison, WI: National Center for Effective Schools Research and Development.

- Lieberman, A. (1996). Creating intentional learning communities. Educational Leadership, 54(3), 31–55.

- McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building school-based teacher learning communities: Professional strategies to improve student achievement. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Miller, S. K. (1982). School learning climate improvement: A case study. Educational Leadership, 40(3): 36-37.

- Neufeld, B., & Roper, D. (2003). Coaching: A strategy for developing instructional capacity, promises, and practicalities. Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute for School Reform. Retrieved June 25, 2007, from http://www.annenberginstitute.org/publications/tlpubs.html#coaching

- Sparks, D. (2002). Designing powerful professional development for teachers and principals. Oxford, OH: National Staff Development Council.

- Stigler, J. W., & Hiebert, J (1997). Understanding and improving classroom mathematics instruction: An overview of the TIMSS video study. Phi Delta Kappan, 79(1), 14–21.

Next Article: Banneker Elementary School: On Course with Reading