Building Literacy Word by Word

Vo•cab´u•lar•y: A sum or stock of words employed by a language, group, individual, or work or in a field of knowledge.

This familiar, five-syllable noun appears to be one of the keys to unlocking student achievement—and increasing self-esteem—for two schools in New Mexico's Bernalillo Public Schools that have been struggling to increase reading comprehension and pull state-mandated assessment scores out of the "teens" with the help of Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL) professionals.

And it has been a challenge, especially since the diverse student population includes a high percentage of American Indian and Hispanic students, several of whom have been exposed to little, if any, English by the time they begin school. Their world is centered in the rural valley, mesa, and mountain landscape of New Mexico that borders bustling Albuquerque and historic, tourist-filled Santa Fe. But many of these children are shy, never having ventured far from their close-knit families and villages, and they could easily become lost in what they perceive to be an intimidating educational system.

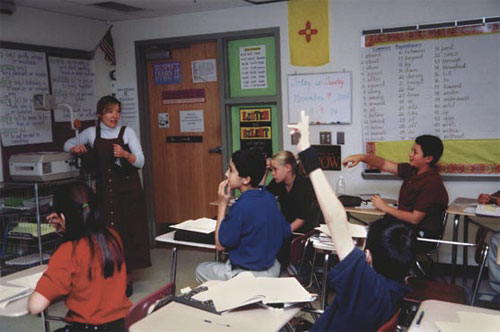

Algodones Elementary School teacher Bobbie Stratton shows her class how to read a tape measure.

The more we learn about teaching, the better the students do.

Bobbie Stratton, Algodones Elementary School

After partnerships with Algodones Elementary School and Bernalillo Middle School were established in 2001 and 2002, respectively, SEDL program associate Ann Neeley, who is the site coordinator for Bernalillo, teamed up with a SEDL reading specialist to regularly visit the schools. They began the cyclic process of obtaining input from educators, parents, and community members; collecting data; setting priorities and identifying a problem; developing strategies to help students overcome that problem; providing professional development opportunities; monitoring teacher and student progress; reviewing data from the monitoring process; and having come full circle, identifying the next concern that requires attention.

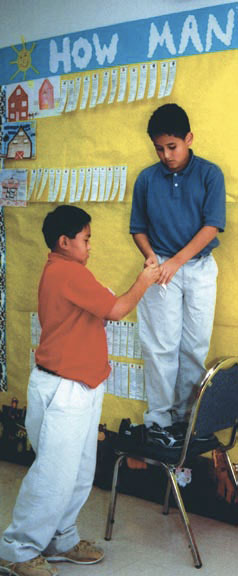

Marcus Garcia and Keenan Rednose place bookmarks for their fifth-grade class on a wall display at Algodones Elementary School. Each bookmark represents a book read and reported on by a student in the class.

"The beginning was rough. We had four administrators in six years, and everyone was in a survival mode," recalls LaTricia Mathis, literacy coach for the 157-student Algodones Elementary School. "When SEDL came in, we saw that we needed to get our ducks in a row, but we didn't even know we had ducks!"

A principal who stayed and recognized the necessity for a cohesive plan of action is Judy Casaus, who appreciates SEDL's expertise and consistently supports her dedicated staff. She enabled development of a plan that has "turned this school around," according to Mathis. That plan focuses on literacy—currently emphasizing vocabulary—in order to ultimately increase student understanding in all fields of study. Educators in both schools have included an oral language component in the curriculum that helps Native American students (who are raised speaking Keres—the sacred and unwritten language of the Pueblo Indians) learn the complexities of English. Mathis calls this oral component "absolutely critical for our Native students."

"I cannot believe how we went from everyone doing his own thing to this level of collaboration," Casaus says. Previously, "our teachers weren't even looking at the data, but by the second year of working with SEDL, we just started flying." The SEDL support "is what kept us going." The principal points out that she and the staff appreciate the critical need for ongoing dialog. She praises her teachers' level of commitment, noting that one summer most of them devoted two hard weeks of unpaid time to hammer out a process that would work for the school. As a result, "achievement is going up."

Neeley is also pleased with the gains made at the elementary school. During her initial visits, there was an apparent lack of direction, with little tracking of students or addressing of their individual needs. "When I walk in that school now, I see reading is important. I see organization. Teachers have created data notebooks on each student, and they can see how the data relates to teaching and the standards," she says. The site coordinator smiles as she describes walls now crowded with student essays and reading accomplishments: "It is not the same place. Teachers are planning more cohesively and study groups reflect that. . . .this is a growing, learning community."

Interviews with Algodones staff reveal an optimism that is pervasive throughout the school. Several point to the administration's emphasis on professional development, policies of inclusion, and the sharing of information as contributing factors in this progress.

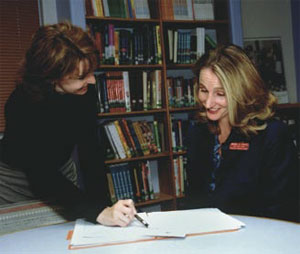

SEDL program associate Stacey Joyner works with Brenda Chavez, one of three literacy coaches at Bernalillo Middle School.

"We have been working on breaking barriers," notes first-grade teacher Bobbie Stratton, "and the more we learn about teaching, the better the students do." Stratton enjoys the small-school environment, in which everyone shares concern for each child. "This staff is really good about meeting student needs; we have assessments in place to see what students need to be working on." When they are evaluated as being at risk," she says, "we assess more, . . . and really use those results and benchmarks to drive curriculum. Through working with SEDL, we have made a difference. And we can continue after the association ends because we know what we're doing now."

Diane Mechego, an educational aide with 27 years of experience, relishes the professional development opportunities she has been offered in the past few years at Algodones Elementary School. She believes that her exposure to the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS) and information presented at other workshops has made her appreciate her role in the teaching process much more.

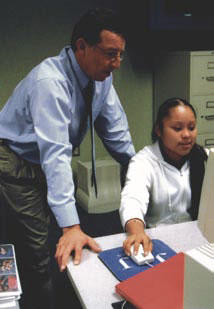

Bernalillo Middle School principal Allan Tapia helps one of his students. His philosophy is “Bottom line—the instructor makes the difference.”

"If we understand the goals, we can be productive," Mechego says. A member of the nearby Santa Ana Pueblo and a native Keres speaker, she understands the obstacles her students face: "Communication skills and vocabulary are just not there. These students haven't been exposed to the English language, and transitioning from Keres thought to English thought is very difficult for them." But she celebrates even the small achievements of her group of at-risk students, whom she continues to teach as they advance to the next grade level.

Literacy coach LaTricia Mathis believes in letting all parents know exactly where their young students stand in terms of skills mastery; she provides older students with the same kind of information about themselves. If a fourth grader is reading at a second-grade level, that information is shared, and is often an eye-opening experience for parents. Most appreciate this candor and often make an effort to encourage reading at home.

It is obvious that something is working at Algodones Elementary School, where fifth graders in line for lunch examine how the competition is shaping up for the month's book-reading contest. They ask their teacher why the 49 books their class has read in the past 10 days are not posted on the colorful display that stretches down the hallway. Students who used to complain, "Library is boring," or ask librarian Teresa Miller "Are you almost done?" as she was reading a story, now gather to check out books when she arrives at school early each morning. She sees anywhere from 18 to 53 eager readers daily now. And test scores continue to rise. In each grade level, Mathis points out growing numbers of students now classified as proficient in the New Mexico Public Education Department Accountability Report. Indeed, this year Algodones met Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) goals. Student proficiency in reading increased from 35.29 percent in school year 2002–2003 to 40 percent in 2003–2004.

Several miles south at Bernalillo Middle School, teachers are making similar gains in their efforts to promote literacy through vocabulary building. The percentage of middle school students proficient in reading rose from 43.26 percent in 2002–2003 to 48.19 percent in 2003–2004.

SEDL program associates Stacey Joyner and Ann Neeley review data with Bernalillo Middle School literacy coach Matt Montaño.

Principal Allan Tapia and his trio of literacy coaches—Brenda Chavez, Jody Marinucci, and Matt Montaño—huddle over a calendar with Ann Neeley and SEDL program associate Stacey Joyner to block time before the school year ends for classroom visits and ongoing meetings with the SEDL staff, each other, and language arts teachers at the 600-student school. They work to adjust their crowded schedules to accommodate the amount of work left to do before the partnership ends in May 2005.

Neeley emphasizes that Tapia's is one of the few secondary schools that incorporates the literacy coach concept for bettering student reading and comprehension. "And he did it with absolutely no money," she says, explaining that the principal did not receive funding for a new position, but called on three of his English teachers to each devote an hour of their days to become coaches.

Exactly what does a literacy coach do? Bernalillo Middle School teachers are learning that he or she becomes a mentor for teachers and provides continued, on-the-job training and guidance so all can become effective reading teachers. They concentrate on theory underlying instruction, demonstration of activities, observation of teachers practicing new lessons, feedback on instruction, and supporting collaboration among teachers. But never do they evaluate teachers. Instead, they provide a safe atmosphere in which to improve instruction.

This fits right into Tapia's philosophy of, "Bottom line: the instructor makes the difference. Delivery of instruction is what's most important." Studies support this reasoning and reveal that if students receive two years of reading instruction from strong, highly qualified, and informed teachers, they develop into successful readers, even if there is little parental reinforcement in the home.

He also maintains that students rise to the level of expectation, and these days, Bernalillo Middle School "has definitely raised the bar." Tapia resolves to keep expectations high and says, "For many years we were sympathetic because of the level of poverty. We thought we were doing students a favor by not demanding they complete homework because they may have to go home after school and spend hours working—for example, chopping wood or babysitting." But, he stresses, "the key to their future is education."

The three literacy coaches have also applied their newfound knowledge to their own classrooms. Marinucci's students are engaged and eager to participate during a discussion of the different sounds vowel and consonant combinations make, which will ultimately improve writing and spelling skills. She challenges students when they make mistakes and encourages others in the class to point out errors in the fast-paced lesson, during which she is constantly keeping students on track and correcting small behavior problems before they escalate. With energy and enthusiasm still high, Marinucci directs her students' attention to a side board, where they identify and discuss prepositional phrases. The teacher makes sure all students understand the material before moving on. She says, "I have learned so much in my work with SEDL—and there is so much more to learn!"

Joyner provides teaching materials to these literacy coaches in the Bernalillo Public Schools and offers suggestions on how to help students overcome vocabulary stumbling blocks. One of the publications SEDL reading specialists produced, "Effective Instructional Strategies for Vocabulary Development," outlines general and specific methods shown to increase word usage and comprehension. A popular, but outdated, method that does little in mastering the approximately 88,000 words required for reading at a ninth-grade level is the copying of definitions from the dictionary, followed by a quiz at the end of the week. As Joyner explains, "It provides only surface-level meaning and often without supporting context."

She suggests other strategies to build vocabulary, both incidentally, through reading and conversation, and directly, by focusing on direct instruction of words or word-learning strategies to extend meaning, gain information from context, teach word parts, and practice, encourage, and reinforce vocabulary knowledge.

Gains he's seen in language skills "really lift my spirits," Bernalillo Middle School literacy coach Matt Montaño says. "Now I access data to impact my teaching, and Ann and Stacey have provided me with information so we can use that data to improve as teachers. They are resources I never expected to have, and they encourage me to be a true leader, respected among my colleagues because of my knowledge."

Leadership is indeed important, agrees Algodones elementary school principal Judy Casaus. For her, SEDL provided just the boost she needed to "look at the whole picture" and become the guide her staff needed in the challenging process of school improvement. "There has to be consistency there," she maintains, "and you need to follow through on everything or else things can fall through the cracks." Principals at both these Bernalillo schools, armed with the knowledge that aligning curriculum, assessment, and instruction is vital for student achievement, feel confident that they will be able to continue their efforts, even without SEDL's regular visits. "We know the lines of communication will remain open," Allan Tapia says, referring not only to SEDL staff, but also to all involved in the ongoing effort to promote literacy.

Bernalillo literacy coach Jody Marinucci models a lesson for one of the middle school teachers.

Pamela Porter is a journalism instructor at New Mexico State University and a freelance writer and photographer. Her work has often appeared in New Mexico Magazine.

Next Article: Early Experience in School Sets the Stage for Later School Success