|

n

the four days of the Winter Meeting, SCIMAST staff presented several

activities to frame the participants' field experiences. The following

summaries show how a few of these activities could be reworked for

students of all ages. They could be used to introduce students to

the field work or to help them sum up their observations. n

the four days of the Winter Meeting, SCIMAST staff presented several

activities to frame the participants' field experiences. The following

summaries show how a few of these activities could be reworked for

students of all ages. They could be used to introduce students to

the field work or to help them sum up their observations.

Since the participants in the Winter Meeting have been coming

together twice a year for at least three years, they know each other

well. Even so, they had not constructed a common understanding of

the material to be studied. The first task SCIMAST staff faced was

to offer ways to help the participants build shared assumptions

about systems.

Describing a System

In the Winter Meeting. In small groups of three or four,

the participants were given envelopes with the names of the general

parts of a system (input, output, feedback mechanisms, components,

subsystems) and the name of a specific system (circulation, transportation,

legislative, school, hospital, McDonalds). The task for each small

group then was to show how the specific system they received illustrated

the general parts common to all systems.

The participants described the system they received on chart paper

and then discussed it among the groups. At the end of the discussion

each participant wrote an operational definition of a system. This

definition was to be refined throughout the four days. In discussions

the definitions were referred to and reworked until the last day.

In the Classroom. Even young students can recognize some parts

of a system, although they may not have the vocabulary to name or

describe those parts. Concepts introduced in class may need to be

discussed again so students can rethink their understanding of systems.

This activity may help students who have already been introduced to

the concepts to think more deeply about them in relation to systems

and the natural world.

Most students will need names of familiar systems. While it may

stretch the thinking of adults and older students to discuss legislative

and respiratory systems together, younger students may be confused

if the teacher has not explained earlier how the systems resemble

each other. In some cases the teacher may need to be very explicit

in eliciting the similarities among the systems and helping children

think about their commonalties.

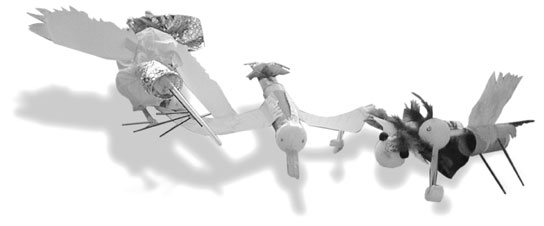

Building a Bird

Marine

Science Institute staff introduced the PDAs to the characteristics

of the barrier island ecosystem and its resident species through

maps, slides, and general descriptions. The participants then began

to work on constructing models of birds that were adapted to the

conditions found in various parts of the Port Aransas system. Long-legged

birds that walk along the shoreline eating small creatures could

be constructed from straws and Styrofoam bodies. Beaks could be

fashioned from macaroni shells. Other items available in the array

of materials--feathers, construction paper, beads, sequins, and

any other items that appealed to their interests--could be used

to form the entire bird. Marine

Science Institute staff introduced the PDAs to the characteristics

of the barrier island ecosystem and its resident species through

maps, slides, and general descriptions. The participants then began

to work on constructing models of birds that were adapted to the

conditions found in various parts of the Port Aransas system. Long-legged

birds that walk along the shoreline eating small creatures could

be constructed from straws and Styrofoam bodies. Beaks could be

fashioned from macaroni shells. Other items available in the array

of materials--feathers, construction paper, beads, sequins, and

any other items that appealed to their interests--could be used

to form the entire bird.

The exercise gave participants an opportunity to demonstrate their

understanding of how creatures' physical adaptations conform to

environmental needs. Discussions, not only with the whole group

but also during the creation of the models, showed shared depth

of understanding. Participants worked out how structure and function

were related in birds' anatomy and indicated that they knew, for

example, that wading birds would need long legs and that the shape

of its bill governs what a bird eats. Using these understandings

they built workable models of, often fanciful, birds.

In the classroom. Students may be tempted to focus on the

inventiveness of their creations, but conversations will reveal

the quality of their thinking about habitat and adaptation. Moving

from group to group while students are constructing their birds

will help the teacher understand their thinking. Students can also

explain their constructions to the whole group in presentations

that become, in essence, performance assessments.

The Town Meeting Simulation

Based on an activity developed by Project Wild (see "To Zone or

not to Zone" in the second edition of Project Wild: K-12 Activity

Guide; available from Project Wild at 707 Conservation Lane, Suite

305, Gaithersburg, MD 20878), the Town Meeting simulation gave participants

an opportunity to reflect on their observations and apply them in

a realistic context. Participants would see that changing part of

a system affects not only that system but also other systems and

their interconnections. The exercise also made clear that all systems,

both those created by humans and by nature, are interconnected.

The simulation can be reworked for almost any age group. The role-playing

aspects make it equally interesting for adults and younger children.

A simulation such as this one could be the culmination of many

different field trips. Students could debate planned changes in

roads around a site, proposals to make an area into a park or to

remove it from the park system, the creation of a nature preserve,

delisting an animal or plant as an endangered species, or similar

subjects connected with their field experience. Ways to adjust this

simulation for school use will be discussed alongside descriptions

of how it played out in the Winter Meeting rather than separately.

Introducing the Issues

Periodically, people in this part of Texas suggest that a channel

should be reopened to connect Corpus Christi Bay to the Gulf of

Mexico. Tourism businesses, fishing enthusiasts, and real estate

interests support creating a channel. Many ecologists oppose the

channel, as do those who worry about safety during a big hurricane,

fiscal conservatives and taxpayer groups, and tourism business-people

in smaller towns who fear that a channel would draw visitors to

Corpus Christi and away from them.

While this activity may appear to be best suited to older students,

it can be altered for children of all ages. As part of their introduction

to the field experience, older students could identify and research

the political, economic, and social issues of the site. The time

devoted to research and presentation, the level of sophistication

of the arguments, and the depth of detail presented will all be

functions of the students' ages. Age-appropriate introductions will

help young students deal with complex issues within this context.

Children could use a simulation as an introduction to the topic

rather than a summing up. A short simulation with different parts

for each child might usefully introduce youngsters to broader concepts

involved in their field trip.

Preparing to Debate

For the Town Meeting simulation, SCIMAST staff prepared extensive

descriptions of the issues connected with the proposed Packery Channel

and developed a stable of personalities to argue for each side.

Supporters and opponents of the channel were more or less even in

number. Participants were to argue before a mock city council made

up of other participants.

Each participant was randomly assigned a character in the controversy

as part of the information packet. If students develop their own

materials, they may want to develop their own characters. Alternatively,

the teacher may expect them, like debate team members, to be able

to support any point of view.

Some participants were cast as members of the city council, one

as the mayor who presided over the meeting. In a classroom, these

roles could be randomly assigned like the others or could be voted

on from the class. After the role players have presented all sides

of the controversy, the city council members and mayor vote on the

project.

In the SCIMAST simulation participants were given 15 minutes to

read their information on the channel controversy and 15 minutes

to caucus in "for" and "against" groups. Students, of course, could

take much longer working to find their own information and forming

advocacy groups within the class. Preparing information on all sides

of issues could be part of their pre-visit work or could be an assignment

when they return to class from the field.

Even with very little time to prepare, the participants presented

various positions fairly by drawing on what they had learned in

the previous days. In a school, cooperation with the civics teacher

or debate coach at this stage could make the field experience interdisciplinary.

Simulation as an Assessment

The simulation is an opportunity for student reflection. As individuals

and in their groups they need to rethink what they have learned

and what meaning it has for them. If it is presented after the field

trip, the simulation can also be an assess-ment. As an assessment,

it allows each student to display his or her learning from the field

and understanding of the broader social and political issues connected

with the environment. Students should be aware of what will be expected

of them both before and during the field experience so they can

be gathering their thoughts in an organized manner with the simulation

as a goal.

The complexity of this activity can deepen for older students.

Students may chose to present position papers and oral arguments

as part of the simulation and as part of the assessment of their

learning. Each student could prepare a portfolio of his or her own

position paper and the research that lead up to it, observations

made at the site, prepatory work that lead up to the field trip,

or other evidence of learning. The final vote could also be included

in all portfolios along with individual discussions of those results.

Closure

After the simulation was over, SCIMAST presented the participants

with several prompts for discussion and reflection:

- How much of the debate on the Packery Channel actually focused

on environmental issues?

- What role did economics and politics play in the debate?

- How can people learn to balance conflicting principles?

- How can we educate students to make good decisions in these

types of situations?

- What happens when you have conflicting scientific data? How

do you decide whom to believe? How do you establish priorities?

In a classroom setting these questions could become the basis

of essays or classroom debates. One or more could form the core

of an assessment protocol, perhaps as questions the teacher could

use to organize feedback to the students.

Copies of the original town meeting activity are available. These

copies are more extensive than the presentation here and include

supporting materials developed by the SCIMAST staff. If you would

like a copy, please contact a SCIMAST staff member or write to

Classroom Compass

Southwest Educational Development Laboratory,

211 E. Seventh St.

Austin, TX 78701-3253

|